| Yuan Longping | |

|---|---|

| 袁隆平 | |

| Born | September 7, 1930 (age 89) Beijing, China |

| Education | High School Affiliated to Nanjing Normal University |

| Alma mater | Southwest Agricultural College |

| Occupation | Agronomist |

| Years active | 1960-present |

| Organization | Hunan Agricultural University |

| Known for | Hybrid rice |

| Spouse(s) | Deng Zhe (m. 1964) |

| Children | 2 |

| Awards | State Preeminent Science and Technology Award 2001 Wolf Prize in Agriculture 2004 World Food Prize 2004 Confucius Peace Prize 2012 |

| Chinese name | |

| Traditional Chinese | 袁隆平 |

| Simplified Chinese | 袁隆平 |

| showTranscriptions |

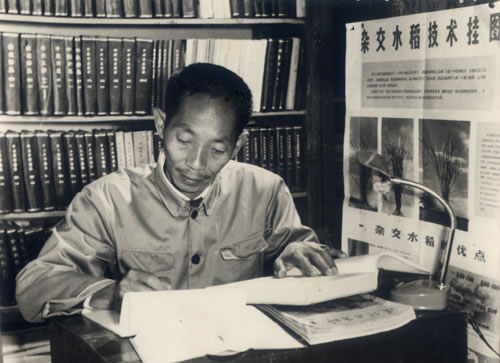

Yuan Longping (Chinese: 袁隆平; born September 7, 1930) is a Chinese agronomist, known for developing the first hybrid rice varieties in the 1970s.

Hybrid rice has since been grown in dozens of countries in Africa, America, and Asia—providing a robust food source in areas with a high risk of famine. For his contributions, Yuan is always called the “Father of Hybrid Rice” by the Chinese media.[1][2]

Contents

- 1Biography

- 2Early stages of hybrid rice experiments

- 3Contributions

- 4Honors and awards

- 5See also

- 6References

- 7Literature

- 8External links

Biography

Yuan was born in Beijing in 1930. His ancestral home is in De’an County, Jiujiang, Jiangxi Province. During the Second Sino-Japanese War and the Chinese Civil War, he moved with his family and attended school in many places, including Hunan, Chongqing, Hankou and Nanjing.

He graduated from Southwest Agricultural College (now part of Southwest University) in 1953 and began his teaching career at an agriculture school in Anjiang, Hunan Province. He married one of his students, Deng Ze (邓则) in 1964,[3][4] they have two children, Yuan Ding’an (袁定安) and Yuan Dingjiang (袁定江).[5]

He came up with an idea for hybridizing rice in the 1960s when a series of natural disasters and harmful political policies (such as the Great Leap Forward) had plunged China into an unprecedented famine that caused the deaths of millions of Chinese citizens.

Since then, Yuan has devoted himself to the research and development of a better rice breed. In 1964, he happened to find a natural rice plant for use in his hybridization experiments that had obvious advantages over other species. Greatly encouraged, he began to study the elements of this particular breed.

The biggest problem by then was having no known method to reproduce hybrid rice in mass quantities, and that was the problem that Yuan set out to solve. In 1964, Yuan created his theory of using a hypothetical naturally-mutated male-sterile strain of rice that he predicted most probably existed for the creation of a new reproductive hybrid rice species, and in two years’ time he managed to successfully find a few individuals of such a mutated male-sterile rice that he could use for his research. Subsequent experiments proved his original theory feasible, making that theory his most important contribution to hybrid rice.

Yuan Longping in 1953 in Southwest University. Yuan in the back row, left three.

Yuan went on to solve more problems than followed from the first. The first experimental hybrid rice species that were cultivated didn’t show any significant advantage over commonly grown species, so Yuan suggested crossbreeding rice with a more distant relative: the wild rice. In 1970, he found a particularly important species of wild rice that he ended up using for the creation of a high-yield hybrid rice species.[citation needed] In 1973, in cooperation with others, he was finally able to establish a complete process for creating and reproducing this high-yield hybrid rice species.

The next year they successfully cultivated a hybrid rice species which had great advantages over conventionally grown rice. It yielded 20 percent more per unit than that of common rice breeds, putting China in the lead worldwide in rice production. For this achievement, Yuan Longping was dubbed the “Father of Hybrid Rice.”[6]

At present, as much as 50 percent of China’s total number of rice paddies grow Yuan Longping’s hybrid rice species and these hybrid rice paddies yield 60 percent of the total rice production in China.[6] Due to Yuan’s hard work, China’s total rice output rose from 56.9 million tons in 1950 to 194.7 million tons in 2017; about 300 billion kilograms of rice has been produced over the last twenty years, compared to the estimated amount that would have been produced without the hybrid rice species. The annual yield increase is enough to feed 60 million additional people.[7]

The “Super Rice” Yuan is currently working on improving has shown a 30 percent higher yield, compared to common rice, with a record yield of 17,055 kilograms per hectare being registered in Yongsheng County in Yunnan Province in 1999.[7]

In January 2014, Yuan said in an interview that genetically modified food is the future direction of food and that he had been working on genetic modification of rice.[8]

Early stages of hybrid rice experiments

Ideology

As recently as the 1950s, two separate theories of heredity were taught in China. One theory was from Gregor Mendel and Thomas Hunt Morgan and was based on the concept of genes and alleles. The other theory was from Soviet Union scientists Ivan Vladimirovich Michurin and Trofim Lysenko which stated that organisms would change over the course of their lives to adapt to environmental changes they experienced and their offspring would then inherit the changes. At the time, China was a communist country, and the government’s official stance on scientific theories was one of “leaning towards the Soviet side”, and any ideology from the Soviet Union was deemed to be the only truth while everything else would be seen as being invalid. Yuan, as an agricultural student at Southwest University, remained skeptical on both theories and started his own experiments to try and come up with his own conclusions.

His first experiment was on the sweet potato. Following Michurin’s theory, he grafted Ipomoea alba (a kind of flower with high Photosynthesis rate and high efficiency in starch production) on to sweet potatoes. Those sweet potatoes grew a lot bigger than the sweet potatoes he hadn’t grafted the alba on to, with the biggest one reaching almost 8kg. However, when he bred these grafted sweet potatoes and planted them for the second generation, the sweet potatoes produced were still normal sweet potatoes with their original leaves, and the alba flower produced by the seeds of the grafted alba/potato hybrid did not grow sweet potatoes. He continued with similar grafting experiments on other plants, but none of the hybridized plants produced offspring with any of the beneficial traits that had been grafted into their parents, which was a complete contradiction of Michurin’s theory. In Yuan’s conclusions to his experiments, he wrote; “I had learned some background of Mendel and Morgan’s theory, and I knew from journal papers that it was proven by experiments and real agricultural applications, such as seedless watermelon. I desired to read more and learn more, but I can only do it secretly.”[9]

Famine

In 1959 China experienced the Great Chinese Famine. Yuan as an agricultural scientist could do little to greatly help people around him in Hunan province. “There was nothing in the field because hungry people took away all the edible things they can find. They eat grass, seeds, Fern roots, or even white clay. At the very extreme.”[citation] Yuan considered applying the inheritance rules onto sweet potatoes and wheat since their fast rate of growth made them the practical solutions for the famine. However, he realized that in Southern China sweet potato was never a part of the daily diet and wheat didn’t grow well in that area. Therefore, he turned his mind to rice.

Heterosis

Back in 1906, geneticist George Harrison Shull did experiments on the hybrid maize. He observed that inbreeding reduced vigor and production among the offspring but crossbreeding did the opposite. Those experiments proved the concept of Heterosis.[10] In the 1950s, geneticist J. C. Stephens and few others utilized the hybrid of two breeds found in Africa and created the high production seeds for sorghum.[11] Those results were inspiring for Yuan. However, maize and sorghum achieve pollination mainly through cross-pollination, while rice is a self-pollinating plant, which would make any crossbreeding attempts difficult, for obvious reasons. In Edmund Ware Sinnott‘s book Principles of Genetics[12], it clearly stated that self-pollinating plants, like wheat and rice, experienced long-term selection both by nature and by human. Therefore, the traits that were inferior were all excluded, and the remaining traits are all superior. He speculated that there would be no advantage in doing cross-breeding for rice. And the nature of self-pollinating make it hard to do cross breed experiments on rice on a large scale.[12]

Contributions

In 1979, his technique for hybrid rice was introduced into the United States, making it the first case of intellectual property rights transfer in the history of the People’s Republic of China.

The United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization 1991 statistics show that 20 percent of the world’s rice output came from 10 percent of the world’s rice fields that grow hybrid rice.

Honors and awards

Four asteroids and a college in China have been named after him.

Yuan won the State Preeminent Science and Technology Award of China in 2000, the Wolf Prize in Agriculture and the World Food Prize in 2004[6]

He is currently the Director-General of the China National Hybrid Rice R&D Center and has been appointed as Professor at Hunan Agricultural University, Changsha.[13] He is a member of the Chinese Academy of Engineering, foreign associate of the U.S. National Academy of Sciences (2006) and the 2006 CPPCC.[13]

Yuan worked as the chief consultant for the FAO in 1991.[13]

source, wikipedia.