By Xuefei Chen Axelsson

Stockholm, Dec. 7(Greenpost)– Nobel Laureate in Literature Svetlana Alexievich Monday gave a very sad yet very striking speech titled On the Battle Lost at Swedish Academy for her Nobel lecture.

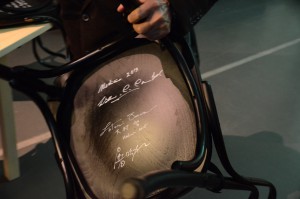

Alexivich signed her signature in the back of a chair at Nobel Museum on Dec. 6. Photo Alexander Muhamoud.

From the very first paragraph, she began to use her novel style to quote the interviewees words to express what kind of people as a Russian, a Belarussian and even Ukrain is like.

” I grew up in the countryside. As children, we loved to play outdoors, but come evening, the voices of tired village women who gathered on benches near their cottages drew us like magnets. None of them had husbands, fathers or brothers.I don’t remember men in our village after World War II: during the war, one out of four Belarussians perished, either fighting at the front or with the partisans.”

Just with a couple of sentences she has summerised about her background.

“After the war, we children lived in a world of women. What I remember most, is that women talked about love, not death. They would tell stories about saying goodbye to the men they loved the day before they went to war, they would talk about waiting for them, and how they were still waiting. Years had passed, but they continued to wait: “I don’t care if he lost his arms and legs, I’ll carry him.” No arms … no legs … I think I’ve known what love is since childhood …”

Then she directly quoted her interviews which present people in front and let the people say.

First voice:

“Why do you want to know all this? It’s so sad. I met my husband during the war. I was in a tank crew that made it all the way to Berlin. I remember, we were standing near the Reichstag – he wasn’t my husband yet – and he says to me: “Let’s get married. I love you.” I was so upset – we’d been living in filth, dirt, and blood the whole war, heard nothing but obscenities. I answered: “First make a woman of me: give me flowers, whisper sweet nothings. When I’m demobilized, I’ll make myself a dress.” I was so upset I wanted to hit him. He felt all of it. One of his cheeks had been badly burned, it was scarred over, and I saw tears running down the scars. “Alright, I’ll marry you,” I said. Just like that … I couldn’t believe I said it … All around us there was nothing but ashes and smashed bricks, in short – war.”

Second voice:

“We lived near the Chernobyl nuclear plant. I was working at a bakery, making pasties. My husband was a fireman. We had just gotten married, and we held hands even when we went to the store. The day the reactor exploded, my husband was on duty at the firе station. They responded to the call in their shirtsleeves, in regular clothes – there was an explosion at the nuclear power station, but they weren’t given any special clothing. That’s just the way we lived … You know … They worked all night putting out the fire, and received doses of radiation incompatible with life. The next morning they were flown straight to Moscow. Severe radiation sickness … you don’t live for more than a few weeks … My husband was strong, an athlete, and he was the last to die. When I got to Moscow, they told me that he was in a special isolation chamber and no one was allowed in. “But I love him,” I begged. “Soldiers are taking care of them. Where do you think you’re going?” “I love him.” They argued with me: “This isn’t the man you love anymore, he’s an object requiring decontamination. You get it?” I kept telling myself the same thing over and over: I love, I love … At night, I would climb up the fire escape to see him … Or I’d ask the night janitors … I paid them money so they’d let me in … I didn’t abandon him, I was with him until the end … A few months after his death, I gave birth to a little girl, but she lived only a few days. She … We were so excited about her, and I killed her … She saved me, she absorbed all the radiation herself. She was so little … teeny-tiny … But I loved them both. How can love be killed? Why are love and death so close? They always come together. Who can explain it? At the grave I go down on my knees …”

Third Voice:

“The first time I killed a German … I was ten years old, and the partisans were already taking me on missions. This German was lying on the ground, wounded … I was told to take his pistol. I ran over, and he clutched the pistol with two hands and was aiming it at my face. But he didn’t manage to fire first, I did …

It didn’t scare me to kill someone … And I never thought about him during the war. A lot of people were killed, we lived among the dead. I was surprised when I suddenly had a dream about that German many years later. It came out of the blue … I kept dreaming the same thing over and over … I would be flying, and he wouldn’t let me go. Lifting off … flying, flying … He catches up, and I fall down with him. I fall into some sort of pit. Or, I want to get up … stand up … But he won’t let me … Because of him, I can’t fly away …

The same dream … It haunted me for decades …

Alexievich has a deep reflection about Russian or socialist history and culture.

“I lived in a country where dying was taught to us from childhood. We were taught death. We were told that human beings exist in order to give everything they have, to burn out, to sacrifice themselves. We were taught to love people with weapons. Had I grown up in a different country, I couldn’t have traveled this path. Evil is cruel, you have to be inoculated against it. We grew up among executioners and victims. Even if our parents lived in fear and didn’t tell us everything – and more often than not they told us nothing – the very air of our life was poisoned. Evil kept a watchful eye on us.

I have written five books, but I feel that they are all one book. A book about the history of a utopia …”

According to her reflection, it seems to me that the communist idea is so deep in the Russian federation that it broke.

Please read yourself for the following and draw your own conclusion.

Twenty years ago, we bid farewell to the “Red Empire” of the Soviets with curses and tears. We can now look at that past more calmly, as an historical experiment. This is important, because arguments about socialism have not died down. A new generation has grown up with a different picture of the world, but many young people are reading Marx and Lenin again. In Russian towns there are new museums dedicated to Stalin, and new monuments have been erected to him.

The “Red Empire” is gone, but the “Red Man,” homo sovieticus, remains. He endures.

My father died recently. He believed in communism to the end. He kept his party membership card. I can’t bring myself to use the word ‘sovok,’ that derogatory epithet for the Soviet mentality, because then I would have to apply it my father and others close to me, my friends. They all come from the same place – socialism. There are many idealists among them. Romantics. Today they are sometimes called slavery romantics. Slaves of utopia. I believe that all of them could have lived different lives, but they lived Soviet lives. Why? I searched for the answer to that question for a long time – I traveled all over the vast country once called the USSR, and recorded thousands of tapes. It was socialism, and it was simply our life. I have collected the history of “domestic,” “indoor” socialism, bit by bit. The history of how it played out in the human soul. I am drawn to that small space called a human being … a single individual. In reality, that is where everything happens.

Right after the war, Theodor Adorno wrote, in shock: “Writing poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric.” My teacher, Ales Adamovich, whose name I mention today with gratitude, felt that writing prose about the nightmares of the 20th century was sacrilege. Nothing may be invented. You must give the truth as it is. A “super-literature” is required. The witness must speak. Nietzsche’s words come to mind – no artist can live up to reality. He can’t lift it.

It always troubled me that the truth doesn’t fit into one heart, into one mind, that truth is somehow splintered. There’s a lot of it, it is varied, and it is strewn about the world. Dostoevsky thought that humanity knows much, much more about itself than it has recorded in literature. So what is it that I do? I collect the everyday life of feelings, thoughts, and words. I collect the life of my time. I’m interested in the history of the soul. The everyday life of the soul, the things that the big picture of history usually omits, or disdains. I work with missing history. I am often told, even now, that what I write isn’t literature, it’s a document. What is literature today? Who can answer that question? We live faster than ever before. Content ruptures form. Breaks and changes it. Everything overflows its banks: music, painting – even words in documents escape the boundaries of the document. There are no borders between fact and fabrication, one flows into the other. Witnessеs are not impartial. In telling a story, humans create, they wrestle time like a sculptor does marble. They are actors and creators.

I’m interested in little people. The little, great people, is how I would put it, because suffering expands people. In my books these people tell their own, little histories, and big history is told along the way. We haven’t had time to comprehend what already has and is still happening to us, we just need to say it. To begin with, we must at least articulate what happened. We are afraid of doing that, we’re not up to coping with our past. In Dostoevsky’sDemons, Shatov says to Stavrogin at the beginning of their conversation: “We are two creatures who have met in boundless infinity … for the last time in the world. So drop that tone and speak like a human being. At least once, speak with a human voice.”

That is more or less how my conversations with my protagonists begin. People speak from their own time, of course, they can’t speak out of a void. But it is difficult to reach the human soul, the path is littered with television and newspapers, and the superstitions of the century, its biases, its deceptions.

I would like to read a few pages from my diaries to show how time moved … how the idea died … How I followed in its path …

1980–1985

I’m writing a book about the war … Why about the war? Because we are people of war – we have always been at war or been preparing for war. If one looks closely, we all think in terms of war. At home, on the street. That’s why human life is so cheap in this country. Everything is wartime.

I began with doubts. Another book about World War II … What for?

On one trip I met a woman who had been a medic during the war. She told me a story: as they crossed Lake Ladoga during the winter, the enemy noticed some movement and began to shoot at them. Horses and people fell under the ice. It all happened at night. She grabbed someone she thought was injured and began to drag him toward the shore. “I pulled him, he was wet and naked, I thought his clothes had been torn off,” she told me. Once on shore, she discovered that she had been dragging an enormous wounded sturgeon. And she let loose a terrible string of obscenities: people are suffering, but animals, birds, fish – what did they do? On another trip I heard the story of a medic from a cavalry squadron. During a battle she pulled a wounded soldier into a shell crater, and only then noticed that he was a German. His leg was broken and he was bleeding. He was the enemy! What to do? Her own guys were dying up above! But she bandaged the German and crawled out again. She dragged in a Russian soldier who had lost consciousness. When he came to, he wanted to kill the German, and when the German came to, he grabbed a machine gun and wanted to kill the Russian. “I’d slap one of them, and then the other. Our legs were all covered in blood,” she remembered. “The blood was all mixed together.”

This was a war I had never heard about. A woman’s war. It wasn’t about heroes. It wasn’t about one group of people heroically killing another group of people. I remember a frequent female lament: “After the battle, you’d walk through the field. They lay on their backs … All young, so handsome. They lay there, staring at the sky. You felt sorry for all of them, on both sides.” It was this attitude, “all of them, on both sides,” that gave me the idea of what my book would be about: war is nothing more than killing. That’s how it registered in women’s memories. This person had just been smiling, smoking – and now he’s gone. Disappearance was what women talked about most, how quickly everything can turn into nothing during war. Both the human being, and human time. Yes, they had volunteered for the front at 17 or 18, but they didn’t want to kill. And yet – they were ready to die. To die for the Motherland. And to die for Stalin – you can’t erase those words from history.

The book wasn’t published for two years, not before perestroika and Gorbachev. “After reading your book no one will fight,” the censor lectured me. “Your war is terrifying. Why don’t you have any heroes?” I wasn’t looking for heroes. I was writing history through the stories of its unnoticed witnesses and participants. They had never been asked anything. What do people think? We don’t really know what people think about great ideas. Right after a war, a person will tell the story of one war, a few decades later, it’s a different war, of course. Something will change in him, because he has folded his whole life into his memories. His entire self. How he lived during those years, what he read, saw, whom he met. What he believes in. Finally, whether is he happy or not. Documents are living creatures – they change as we change.

I’m absolutely convinced that there will never again be young women like the war-time girls of 1941. This was the high point of the “Red” idea, higher even than the Revolution and Lenin. Their Victory still eclipses the GULAG. I dearly love these women. But you couldn’t talk to them about Stalin, or about the fact that after the war, whole trainloads of the boldest and most outspoken victors were sent straight to Siberia. The rest returned home and kept quiet. Once I heard: “The only time we were free was during the war. At the front.” Suffering is our capital, our natural resource. Not oil or gas – but suffering. It is the only thing we are able to produce consistently. I’m always looking for the answer: why doesn’t our suffering convert into freedom? Is it truly all in vain? Chaadayev was right: Russia is a country without memory, it’s a space of total amnesia, a virgin consciousness for criticism and reflection.

But great books are piled up beneath our feet.

1989

I’m in Kabul. I don’t want to write about war anymore. But here I am in a real war. The newspaper Pravda says: “We are helping the fraternal Afghan people build socialism.” People of war and objects of war are everywhere. Wartime.

They wouldn’t take me into battle yesterday: “Stay in the hotel, young lady. We’ll have to answer for you later.” I’m sitting in the hotel, thinking: there is something immoral in scrutinizing other people’s courage and the risks they take. I’ve been here for two weeks and I can’t shake the feeling that war is a product of masculine nature, which is unfathomable to me. But the everyday accessories of war are grand. I discovered for myself that weapons are beautiful: machine guns, mines, tanks. Man has put a lot of thought into how best to kill other men. The eternal dispute between truth and beauty. They showed me a new Italian mine, and my “feminine” reaction was: “It’s beautiful. Why is it beautiful?” They explained to me precisely, in military terms: if someone drives over or steps on this mine just so … at a certain angle … there would be nothing left but half a bucket of flesh. People talk about abnormal things here as though they’re normal, taken for granted. Well, you know, it’s war … No one is driven insane by these pictures – for instance, there’s a man lying on the ground who was killed not by the elements, not by fate, but by another man.

I watched the loading of a “black tulip” (the airplane that carries casualties back home in zinc coffins). The dead are often dressed in old military uniforms from the ‘40s, with jodhpurs; sometimes there aren’t even enough of those to go around. The soldiers were chatting: “They just delivered some new ones to the fridges. It smells like boar gone bad.” I am going to write about this. I’m afraid that no one at home will believe me. Our newspapers just write about friendship alleys planted by Soviet soldiers.

I talk to the guys. Many have come voluntarily. They asked to come here. I note that most are from educated families, the intelligentsia – teachers, doctors, librarians – in a word, bookish people. They sincerely dreamed of helping the Afghan people build socialism. Now they laugh at themselves. I was shown a place at the airport where hundreds of zinc coffins sparkle mysteriously in the sun. The officer accompanying me couldn’t help himself: “Who knows … my coffin might be over there … They’ll stick me in it … What am I fighting for here?” His own words scared him and he immediately said: “Don’t write that down.”

At night I dream of the dead, they all have looks of surprise on their faces: what, you mean I was killed? Have I really been killed?”

I drove to a hospital for Afghan civilians with a group of nurses – we brought presents for the children. Toys, candy, cookies. I had about five teddy bears. We arrived at the hospital, a long barracks. No one has more than a blanket for bedding. A young Afghan woman approached me, holding a child in her arms. She wanted to say something – over the last ten years almost everyone here has learned to speak a little Russian – and I handed the child a toy, which he took with his teeth. “Why his teeth?” I asked in surprise. She pulled the blanket off his tiny body – the little boy was missing both arms. “It was when your Russians bombed.” Someone held me up as I began to fall.

I saw our “Grad” rockets turn villages into plowed fields. I visited an Afghan cemetery, which was about the length of one of their villages. Somewhere in the middle of the cemetery an old Afghan woman was shouting. I remembered the howl of a mother in a village near Minsk when they carried a zinc coffin into the house. The cry wasn’t human or animal … It resembled what I heard at the Kabul cemetery …

I have to admit that I didn’t become free all at once. I was sincere with my subjects, and they trusted me. Each of us has his or her own path to freedom. Before Afghanistan, I believed in socialism with a human face. I came back from Afghanistan free of all illusions. “Forgive me father,” I said when I saw him. “You raised me to believe in communist ideals, but seeing those young men, recent Soviet schoolboys like the ones you and Mama taught (my parents were village school teachers), kill people they don’t know, on foreign territory, was enough to turn all your words to ash. We are murderers, Papa, do you understand!?” My father cried.

Many people returned free from Afghanistan. But there are other examples, too. There was a young fellow in Afghanistan who shouted to me: “You’re a woman, what do you understand about war? You think that people die a pretty death in war, like they do in books and movies? Yesterday my friend was killed, he took a bullet in the head, and kept running another ten meters, trying to catch his own brains …” Seven years later, the same fellow is a successful businessman, who likes to tell stories about Afghanistan. He called me: “What are your books for? They’re too scary.” He was a different person, no longer the young man I’d met amid death, who didn’t want to die at age twenty …

I ask myself what kind of book I want to write about war. I’d like to write a book about a person who doesn’t shoot, who can’t fire on another human being, who suffers at the very idea of war. Where is he? I haven’t met him.

1990–1997

Russian literature is interesting in that it is the only literature to tell the story of an experiment carried out on a huge country. I am often asked: why do you always write about tragedy? Because that’s how we live. We live in different countries now, but “Red” people are everywhere. They come out of that same life, and have the same memories.

I resisted writing about Chernobyl for a long time. I didn’t know how to write about it, what instrument to use, how to approach the subject. The world had almost never heard anything about my little country, tucked away in a corner of Europe, but now its name was on everyone’s tongue. We, Belarussians, had become the people of Chernobyl. The first to encounter the unknown. It was clear now: besides communist, ethnic, and new religious challenges, there are more global, savage challenges in store for us, though for the moment they are invisible. Something opened a little bit after Chernobyl …

I remember an old taxi driver swearing in despair when a pigeon hit the windshield: “Every day, two or three birds smash into the car. But the newspapers say the situation is under control.”

The leaves in city parks were raked up, taken out of town, and buried. The ground was cut out of contaminated areas and buried, too – earth was buried in the earth. Firewood was buried, and grass. Everyone looked a little crazy. An old beekeeper told me: “I went out into the garden that morning, and something was missing, a familiar sound. There weren’t any bees. I couldn’t hear a single bee. Not a one! What? What’s going on? They didn’t fly out on the second day either, or on the third … Then we were told that there was an accident at the nuclear station – and it isn’t far away. But we didn’t know anything about it for a long time. The bees knew, but we didn’t.” All the information about Chernobyl in the newspapers was in military language: explosion, heroes, soldiers, evacuation … The KGB worked right at the station. They were looking for spies and saboteurs. Rumors circulated that the accident was planned by western intelligence services in order to undermine the socialist camp. Military equipment was on its way to Chernobyl, soldiers were coming. As usual, the system worked like it was war time, but in this new world, a soldier with a shiny new machine gun was a tragic figure. The only thing he could do was absorb large doses of radiation and die when he returned home.

Before my eyes pre-Chernobyl people turned into the people of Chernobyl.

You couldn’t see the radiation, or touch it, or smell it … The world around was both familiar and unfamiliar. When I traveled to the zone, I was told right away: don’t pick the flowers, don’t sit on the grass, don’t drink water from a well … Death hid everywhere, but now it was a different sort of death. Wearing a new mask. In an unfamiliar guise. Old people who had lived through the war were being evacuated again. They looked at the sky: “The sun is shining … There’s no smoke, no gas. No one’s shooting. How can this be war? But we have to become refugees.”

In the mornings everyone would grab the papers, greedy for news, and then put them down in disappointment. No spies had been found. No one wrote about enemies of the people. A world without spies and enemies of the people was also unfamiliar. This was the beginning of something new. Following on the heels of Afghanistan, Chernobyl made us free people.

For me the world parted: inside the zone I didn’t feel Belarussian, or Russian, or Ukrainian, but a representative of a biological species that could be destroyed. Two catastrophes coincided: in the social sphere, the socialist Atlantis was sinking; and on the cosmic – there was Chernobyl. The collapse of the empire upset everyone. People were worried about everyday life. How and with what to buy things? How to survive? What to believe in? What banners to follow this time? Or do we need to learn to live without any great idea? The latter was unfamiliar, too, since no one had ever lived that way. Hundreds of questions faced the “Red” man, but he was on his own. He had never been so alone as in those first days of freedom. I was surrounded by people in shock. I listened to them …

I close my diary …

What happened to us when the empire collapsed? Previously, the world had been divided: there were executioners and victims – that was the GULAG; brothers and sisters – that was the war; the electorate – was part of technology and the contemporary world. Our world had also been divided into those who were imprisoned and those who imprisoned them; today there’s a division between Slavophiles and Westernizers, “fascist-traitors” and patriots. And between those who can buy things and those who can’t. The latter, I would say, was the cruelest of the ordeals to follow socialism, because not so long ago everyone had been equal. The “Red” man wasn’t able to enter the kingdom of freedom he had dreamed of around his kitchen table. Russia was divvied up without him, and he was left with nothing. Humiliated and robbed. Aggressive and dangerous.

Here are some of the comments I heard as I traveled around Russia …

“Modernization will only happen here with sharashkas, those prison camps for scientists, and firing squads.”

“Russians don’t really want to be rich, they’re even afraid of it. What does a Russian want? Just one thing: for no one else to get rich. No richer than he is.”

“There aren’t any honest people here, but there are saintly ones.”

“We’ll never see a generation that hasn’t been flogged; Russians don’t understand freedom, they need the Cossack and the lash.”

“The two most important words in Russian are ‘war’ and ‘prison.’ You steal something, have some fun, they lock you up … you get out, and then end up back in jail …”

“Russian life needs to be vicious and despicable. Then the soul is uplifted, it realizes that it doesn’t belong to this world … The filthier and bloodier things are, the more room there is for the soul …”

“No one has the energy for a new revolution, or the craziness. No spirit. Russians need the kind of idea that will send shivers down your spine …”

“So our life just dangles between bedlam and the barracks. Communism didn’t die, the corpse is still alive.”

I will take the liberty of saying that we missed the chance we had in the 1990s. The question was posed: what kind of country should we have? A strong country, or a worthy one where people can live decently? We chose the former – a strong country. Once again we are living in an era of power. Russians are fighting Ukrainians. Their brothers. My father is Belarussian, my mother, Ukrainian. That’s the way it is for many people. Russian planes are bombing Syria …

A time full of hope has been replaced by a time of fear. The era has turned around and headed back in time. The time we live in now is second-hand …

Sometimes I am not sure that I’ve finished writing the history of the “Red” man …

I have three homes: my Belarussian land, the homeland of my father, where I have lived my whole life; Ukraine, the homeland of my mother, where I was born; and Russia’s great culture, without which I cannot imagine myself. All are very dear to me. But in this day and age it is difficult to talk about love.

Translation: Jamey Gambrell

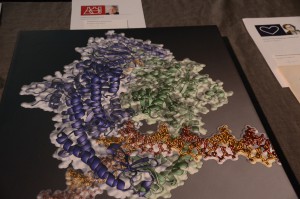

The four Laureates receive their awards at a ceremony in the Swedish Parliament in Stockholm last Thursday.

The four Laureates receive their awards at a ceremony in the Swedish Parliament in Stockholm last Thursday.